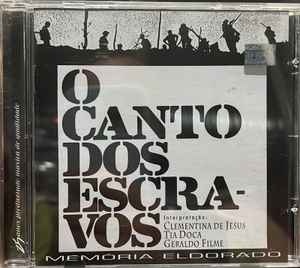

O Canto Dos Escravos

by Clementina De Jesus / Tia Doca / Geraldo Filme

Review

**O Canto Dos Escravos: A Sacred Trinity of Afro-Brazilian Resistance**

The echoes of "O Canto Dos Escravos" continue to reverberate through Brazilian music nearly five decades after its release, a testament to the raw power of three voices united in preserving the ancestral songs that built a nation. This isn't just an album—it's an archaeological dig into the soul of Brazil, unearthing melodies that survived the Middle Passage and found new life in the favelas and terreiros of Rio de Janeiro.

Today, this 1970 recording stands as one of the most important documents of Afro-Brazilian musical heritage ever captured on vinyl. Music scholars and collectors treat it with the reverence typically reserved for religious artifacts, and rightfully so. The album has influenced generations of Brazilian artists, from Caetano Veloso to contemporary MPB singers who continue to mine its depths for inspiration. Its inclusion in countless "essential Brazilian music" lists isn't mere tokenism—it's recognition of a work that fundamentally altered how Brazil understood its own musical DNA.

The genius of "O Canto Dos Escravos" lies not in technical virtuosity or sophisticated arrangements, but in its unflinching authenticity. These aren't museum pieces performed by conservatory-trained voices; they're living, breathing songs delivered by artists who carried them in their bones. The production is deliberately sparse—just voices, hand percussion, and the occasional guitar—allowing the raw emotional power of these ancestral chants to pierce through without ornamentation or artifice.

Among the album's treasures, "Benguelê" stands as perhaps the most haunting track, with Clementina's weathered voice leading a call-and-response that seems to channel spirits from across centuries. Her vocal style here is less singing than summoning, each note carrying the weight of collective memory. "Caxangá" showcases the trio's remarkable chemistry, their voices interweaving like conversations between old friends who've shared lifetimes of stories. Meanwhile, "Jongo da Serrinha" captures the hypnotic rhythm of the jongo dance, transforming the listener's living room into a sacred circle where the past and present collapse into one eternal moment.

Tia Doca's contributions throughout the album reveal a voice seasoned by decades of informal performances in Rio's working-class neighborhoods, while Geraldo Filme brings a masculine counterpoint that grounds the more ethereal moments. Together, they create a sonic tapestry that feels both ancient and immediate, familiar yet mysterious.

The album's origins trace back to the cultural awakening of late 1960s Brazil, when intellectuals and artists began recognizing that the country's most profound musical traditions were disappearing with their elderly practitioners. Clementina de Jesus had already emerged from decades of obscurity to become a celebrated figure in Rio's cultural scene, her "discovery" in the mid-1960s sparking renewed interest in traditional Afro-Brazilian forms. Producer Hermínio Bello de Carvalho, recognizing the urgency of documenting these vanishing traditions, assembled this unlikely trinity to preserve songs that had survived primarily through oral transmission in Rio's black communities.

The musical styles represented span the breadth of Afro-Brazilian expression: jongos from the coffee plantations of the Paraíba Valley, party songs from Rio's favelas, work chants that once synchronized the labor of enslaved Africans, and religious songs from Candomblé and Umbanda ceremonies. This isn't folklore tourism—it's cultural archaeology performed by living practitioners who understood these songs not as historical curiosities but as vital expressions of resistance and identity.

What makes "O Canto Dos Escravos" enduringly powerful is its refusal to sanitize or romanticize its source material. These songs carry the full weight of their origins—the pain of displacement, the defiance of survival, the joy found in community, and the spiritual sustenance that enabled a people to endure centuries of dehumanization while maintaining their cultural identity. When Clementina's voice cracks with emotion or when the trio's harmonies achieve an otherworldly resonance, you're not just hearing music—you're witnessing the transmission of cultural DNA across generations.

In an era when world music often feels processed and packaged for global consumption, "O Canto Dos Escravos" remains defiantly uncompromising. It demands active listening, cultural curiosity, and emotional engagement. This is music that changes you, that expands your understanding of what human expression

Listen

Login to add to your collection and write a review.

User reviews

- No user reviews yet.