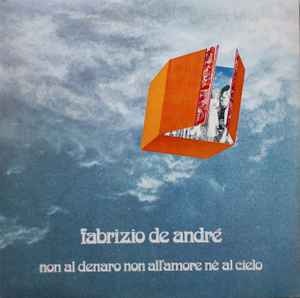

Non Al Denaro, Non All'amore Né Al Cielo

Review

In the pantheon of Italian singer-songwriters, few figures loom as large as Fabrizio De André, and nowhere is his genius more crystalline than on 1971's "Non Al Denaro, Non All'amore Né Al Cielo" – a title that translates to "Not to Money, Not to Love, Nor to Heaven," immediately signaling the album's unflinching rejection of society's holy trinities. This masterwork arrived at a pivotal moment in De André's career, following his breakthrough albums of the late '60s and preceding his folk-rock experiments with Premiata Forneria Marconi. It stands as perhaps his most cohesive artistic statement, a collection that transforms Edgar Lee Masters' "Spoon River Anthology" into a distinctly Italian meditation on death, hypocrisy, and human frailty.

The genesis of this album traces back to De André's discovery of Masters' 1915 poetry collection, which presented the posthumous confessions of residents from the fictional American town of Spoon River. Rather than simply translating these epitaphs, De André embarked on a more ambitious project – reimagining them through the lens of Italian provincial life, creating a musical cemetery where the dead speak their truths with devastating honesty. Working with his frequent collaborator Nicola Piovani, who provided the musical arrangements, De André crafted songs that feel both ancient and immediate, rooted in folk tradition yet thoroughly modern in their psychological penetration.

Musically, the album represents De André at his most austere and powerful. The arrangements are deliberately sparse – acoustic guitars, subtle orchestration, and the occasional flourish of strings or woodwinds – allowing De André's weathered baritone and the weight of his words to dominate. This isn't the baroque complexity of his later works or the traditional folk stylings of his earlier albums, but something altogether more haunting: a kind of chamber music for the damned, where every instrumental choice serves the narrative thrust of these posthumous confessions.

The album opens with "Il Giudice" (The Judge), a scathing indictment of judicial corruption that sets the tone for what follows – a parade of hypocrites, dreamers, and broken souls laying bare their secrets from beyond the grave. De André's genius lies in his ability to find compassion even for his most despicable characters; the judge may be corrupt, but his confession reveals the human cost of his compromises. This empathy reaches its apex in "Un Ottico" (An Optician), where a man who spent his life helping others see clearly admits to his own blindness about love and meaning.

"La Collina" stands as perhaps the album's most devastating track, a meditation on suicide that avoids both sensationalism and sentimentality. De André's delivery is matter-of-fact, almost conversational, making the song's emotional impact all the more profound. Equally powerful is "Un Chimico" (A Chemist), which uses the metaphor of chemical reactions to explore the explosive nature of repressed desire and social conformity. The album's centerpiece might be "Il Suonatore Jones" (Jones the Player), a meta-textual moment where De André directly addresses the act of artistic creation, questioning whether art can truly capture life's complexity or merely provides beautiful distraction from its harsh realities.

The production, overseen by De André himself, achieves a remarkable intimacy. These songs feel like whispered confessions in a darkened room, with every breath and guitar string audible. The recording captures the essence of De André's live performances – that sense of being in the presence of a master storyteller who commands attention through sheer force of personality and artistic vision.

Nearly five decades after its release, "Non Al Denaro, Non All'amore Né Al Cielo" remains a towering achievement in European popular music. Its influence on subsequent generations of Italian singer-songwriters cannot be overstated – from Francesco Guccini to Vinicio Capossela, countless artists have drawn inspiration from De André's ability to marry literary sophistication with musical accessibility. The album's themes of social hypocrisy, spiritual emptiness, and the search for authentic meaning feel, if anything, more relevant in our current age of manufactured personas and digital facades.

This is essential listening for anyone interested in the intersection of literature and popular music, a work that proves the album format's capacity for serious artistic statement. De André created something rare here: a concept album that never feels forced or pretentious, where every song serves both the larger narrative and stands alone as a complete artistic

Listen

Login to add to your collection and write a review.

User reviews

- No user reviews yet.