No Room For Squares

by Hank Mobley

Review

**No Room For Squares: Hank Mobley's Hard Bop Masterpiece**

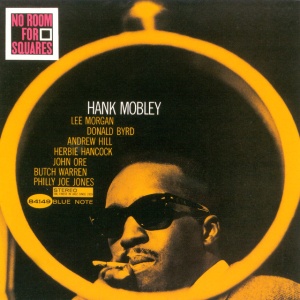

In the annals of Blue Note Records' legendary catalog, few albums capture the essence of hard bop's golden age quite like Hank Mobley's "No Room For Squares." Released in 1963, this smoking session finds the Tennessee tenor saxophonist at the absolute peak of his powers, leading a quintet through seven tracks of pure, unadulterated jazz fire that would cement his reputation as one of the most underrated voices in the genre's history.

By the time Mobley entered Rudy Van Gelder's Englewood Cliffs studio on March 7, 1963, he was already a Blue Note veteran with over a decade of sideman work under his belt. He'd cut his teeth with Max Roach, Dizzy Gillespie, and Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, developing a distinctive tone that split the difference between the cool sophistication of Stan Getz and the fiery intensity of Sonny Rollins. But "No Room For Squares" marked a creative watershed moment – Mobley the composer finally catching up with Mobley the improviser.

The album's title track opens with a deceptively simple melody that unfolds into something far more complex, showcasing Mobley's gift for crafting tunes that sound effortless but reveal new layers with each listen. His tenor sax tone here is warm molasses poured over broken glass – smooth and inviting, yet with an edge that cuts right through the mix. The rhythm section of bassist Butch Warren and drummer Philly Joe Jones locks into an irresistible groove while pianist Andrew Hill provides harmonic colors that range from crystalline to mysterious.

But it's "Up a Step" where the album truly catches fire. Hill's angular piano intro gives way to one of Mobley's most inspired compositions, a minor-key burner that allows each member of the quintet to stretch out. Mobley's solo here is a clinic in melodic development – he takes a simple motif and twists it through every conceivable permutation, building tension with the patience of a master storyteller. When Hill takes his turn, his left-hand comping creates a rhythmic undertow that pulls the entire band forward.

The ballad "Old World, New Imports" reveals another facet of Mobley's artistry. Here, his saxophone becomes almost conversational, each phrase carefully considered and emotionally weighted. It's the kind of performance that separates the true jazz masters from the merely technically proficient – Mobley doesn't just play the changes, he inhabits them, finding the human drama lurking within the chord progressions.

Trumpeter Donald Byrd, Mobley's frequent collaborator and fellow Blue Note stalwart, proves the perfect foil throughout the session. His bright, articulate tone provides an ideal contrast to Mobley's earthier approach, and their exchanges on tracks like "Carolyn" crackle with the kind of telepathic communication that only comes from years of shared bandstands. When they lock into harmony on the head arrangements, it's like hearing two sides of the same musical conversation.

The album's production bears the hallmarks of the Blue Note aesthetic at its finest. Alfred Lion's A&R sensibilities ensured that every composition served the greater whole, while Van Gelder's engineering captured the quintet with startling intimacy. You can practically feel the cigarette smoke and hear the ice clinking in glasses – this is jazz as it was meant to be experienced, in real time and up close.

Tragically, "No Room For Squares" would prove to be something of a creative peak for Mobley. While he continued recording prolifically throughout the 1960s, drug problems and the changing musical landscape would gradually marginalize his influence. The rise of free jazz and fusion left little room for his brand of melody-driven hard bop, and by the 1970s, he was largely forgotten by all but the most devoted jazz fans.

Today, however, "No Room For Squares" stands as a testament to the enduring power of Mobley's musical vision. In an era when jazz musicians are increasingly looking backward for inspiration, this album serves as a masterclass in how to honor tradition while pushing it forward. Every note feels necessary, every solo serves the song, and the overall effect is both timeless and utterly of its moment. For anyone seeking to understand what made hard bop such a vital force in American music, there's definitely room for this square in your collection.

Listen

Login to add to your collection and write a review.

User reviews

- No user reviews yet.