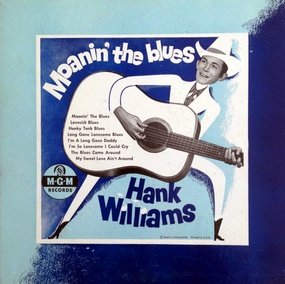

Moanin' The Blues

Review

There's something almost cruelly ironic about the title "Moanin' The Blues" when applied to Hank Williams' posthumous 1952 collection. Here was a man who had spent his brief, meteoric career perfecting the art of the moan—whether it was the lonesome wail of "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry" or the desperate pleading of "Your Cheatin' Heart"—and now MGM Records was packaging his pain for mass consumption just months after his tragic death on New Year's Day 1953.

The album emerged from the vaults as country music was grappling with the sudden loss of its most authentic voice. Williams had died at 29, slumped in the back of a Cadillac somewhere between Bristol, Tennessee and Canton, Ohio, leaving behind a catalogue that would define country music's emotional vocabulary for generations. "Moanin' The Blues" wasn't conceived as a cohesive artistic statement—rather, it was MGM's attempt to capitalise on the posthumous mythology already forming around the Hillbilly Shakespeare.

What makes this collection particularly fascinating is how it captures Williams at his most raw and unvarnished. These aren't the polished Nashville productions that would soon dominate country radio, but rather intimate snapshots of a man wrestling with demons that would ultimately consume him. The album draws from various recording sessions between 1950 and 1952, creating an inadvertent portrait of an artist in decline—though his songwriting remained as sharp as a broken bottle.

The centrepiece, "Moanin' The Blues" itself, is vintage Williams—a slow-burning lament that showcases his ability to wring genuine pathos from simple chord progressions. His voice, always more instrument than mere delivery system, carries the weight of genuine experience. There's no artifice here, no calculated attempt at authenticity. When Williams sings about heartbreak, you believe every syllable because he's lived every syllable.

"Half as Much" stands as perhaps the album's most commercially successful track, though calling it commercial feels almost insulting to its emotional honesty. Co-written with Curley Williams (no relation), it's a masterclass in country songwriting economy—maximum emotional impact delivered through minimal means. The steel guitar weeps in all the right places while Hank's voice navigates the melody with the confidence of a man who understood that restraint often speaks louder than bombast.

Equally compelling is "Honky Tonk Blues," which finds Williams exploring the seedier side of American nightlife with the observational skills of a backwoods Balzac. The song's protagonist isn't celebrating the honky-tonk lifestyle—he's trapped by it, and Williams' delivery suggests he knew something about that particular prison. The rhythm section keeps things moving at a pace that suggests restlessness rather than celebration, while the lyrics paint pictures of neon-lit desperation that would influence everyone from George Jones to Jason Isbell.

"Jambalaya (On the Bayou)" provides the album's most upbeat moment, though even here there's an undercurrent of melancholy. Williams' fascination with Cajun culture wasn't mere tourism—it reflected his broader understanding that American music was a mongrel art form, best when it acknowledged its diverse influences. The song bounces along with infectious energy, but Williams' vocal carries hints of the world-weariness that permeated his later work.

The production throughout maintains the stripped-down aesthetic that made Williams' music so powerful. Jerry Rivers' fiddle and Don Helms' steel guitar create a sonic landscape that's distinctly American—wide open spaces punctuated by moments of intense intimacy. The rhythm section, anchored by bassist Hillous Butrum, provides steady support without ever overwhelming Williams' voice or the emotional content of the songs.

Sixty-plus years later, "Moanin' The Blues" endures not as a historical curiosity but as a living document of American music at its most essential. Every country artist who's ever tried to locate genuine emotion within traditional song structures owes a debt to these recordings. From Johnny Cash's prison concerts to Sturgill Simpson's psychedelic explorations, the through-line leads back to Williams' ability to make the personal universal without sacrificing specificity.

The album's legacy lies not in its commercial success—though it certainly achieved that—but in its demonstration that authenticity cannot be manufactured. Williams wasn't playing a character; he was revealing himself, and that revelation continues to resonate because human pain, like human joy, transcends temporal boundaries. "

Listen

Login to add to your collection and write a review.

User reviews

- No user reviews yet.