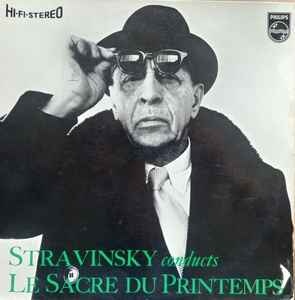

Stravinsky Conducts Le Sacre Du Printemps

by Igor Stravinsky / Columbia Symphony Orchestra

Review

There's something deliciously perverse about Igor Stravinsky conducting his own musical Molotov cocktail some fifty years after it nearly caused a riot at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. By 1960, when this Columbia Symphony Orchestra recording was made, the composer had lived long enough to witness his once-scandalous masterpiece transform from revolutionary manifesto into establishment orthodoxy – a journey that might have amused the mischievous Russian more than it disappointed him.

The original 1913 premiere of *Le Sacre du Printemps* remains classical music's most notorious opening night, with audience members reportedly hurling vegetables and trading punches over Stravinsky's savage rhythms and Nijinsky's primal choreography. The work's violent depiction of pagan ritual – culminating in a virgin dancing herself to death – was so shocking that it overshadowed the ballet's actual choreographic disaster. Yet here, decades later, is the same composer, now in his late seventies, calmly wielding the baton over his own creation with the measured authority of a master craftsman examining a perfectly engineered timepiece.

What emerges from this collaboration between composer and orchestra is nothing short of revelatory. Stravinsky's conducting style was never about theatrical gestures or romantic indulgence – he approached his scores with the precision of a Swiss watchmaker and the rhythmic instincts of a jazz drummer. The Columbia Symphony Orchestra, assembled specifically for recording purposes from Los Angeles's finest session musicians, responds with playing that's both technically immaculate and surprisingly raw when the music demands it.

The opening bassoon solo that launches "The Adoration of the Earth" immediately establishes this recording's unique character. Under Stravinsky's direction, it emerges not as the exotic bird call that lesser conductors often emphasize, but as something more unsettling – a voice from humanity's prehistoric memory. When the full orchestra crashes in with those infamous irregular accents, the effect is less about shock value than about the inexorable pull of ritual itself.

"The Augurs of Spring" – perhaps the work's most recognizable section with its relentless, hammering chords – becomes a study in controlled violence under Stravinsky's baton. Where other conductors might push for maximum brutality, the composer finds something more disturbing: the mechanical precision of ancient ceremony. The strings attack their instruments with surgical precision, while the brass section delivers pronouncements that sound like geological shifts rather than mere musical phrases.

The work's more mysterious passages reveal Stravinsky's intimate understanding of his own harmonic language. "Ritual of the Rival Tribes" unfolds with an almost conversational quality, as if the composer is explaining his own musical logic in real time. The interweaving woodwind lines in "Procession of the Sage" achieve a transparency that allows every voice to speak clearly while maintaining the music's essential savagery.

But it's in "The Sacrifice" – the ballet's apocalyptic second part – where this recording truly transcends mere documentation. "The Chosen One" emerges not as victim but as protagonist in her own terrifying destiny. Stravinsky shapes the music's irregular meters and violent orchestral outbursts into something that feels less like chaos than like the universe itself coming unhinged according to some cosmic plan.

The final "Sacrificial Dance" stands as perhaps the most convincing argument for composer-conducted recordings ever captured on disc. Every impossible rhythm change, every orchestral pile-up, every moment where the music seems to devour itself feels not just inevitable but necessary. The Columbia Symphony's execution is flawless, but more importantly, it serves the music's deeper purpose – to make civilized listeners confront something primal and unsettling within themselves.

This recording's legacy has only grown more significant with time. While countless conductors have since tackled *Le Sacre* with varying degrees of success, none can claim the authority that comes from having lived with this music for half a century. Stravinsky's interpretation remains the definitive statement – not because it's the most exciting or the most technically polished, but because it reveals the work's true nature as something far more complex than mere musical primitivism.

In an age of increasingly homogenized classical recordings, this document stands as a reminder that the most revolutionary music requires not just technical mastery, but the kind of deep understanding that only comes from having written every note yourself.

Listen

Login to add to your collection and write a review.

User reviews

- No user reviews yet.