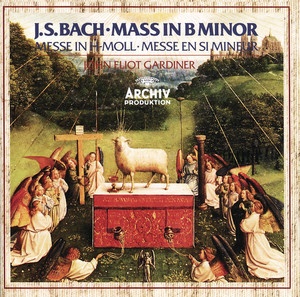

J.S.Bach: Mass In B Minor

by John Eliot Gardiner / English Baroque Soloists / Monteverdi Choir

Review

**★★★★★**

There are moments in recorded music history when the stars align—when the right conductor meets the right ensemble at precisely the right moment in musical evolution. John Eliot Gardiner's 1985 recording of Bach's Mass in B Minor with the English Baroque Soloists and Monteverdi Choir represents one of those lightning-in-a-bottle instances, a performance so definitive it practically rewrote the rulebook for how we approach this towering monument of sacred music.

Bach's Mass in B Minor has always been something of an enigma wrapped in sublimity. The composer never heard it performed in its entirety—hell, he probably never intended it to be. Assembled over decades from various sources, including recycled material from earlier cantatas, it's less a cohesive liturgical work than Bach's ultimate statement on the possibilities of choral writing. Think of it as the *Sgt. Pepper's* of the Baroque era, except instead of psychedelic pop, you get two hours of the most sophisticated counterpoint ever committed to paper.

By the 1980s, the early music movement was hitting its stride, and Gardiner was emerging as its most charismatic evangelist. His approach stripped away centuries of accumulated romantic interpretation, revealing Bach's architecture in all its mathematical beauty. Where previous generations had thrown massive choirs and orchestras at the Mass, Gardiner deployed surgical precision—a chamber choir of just 24 voices and a period instrument orchestra that could turn on a dime.

The results are nothing short of revelatory. From the opening "Kyrie eleison," Gardiner establishes a sense of urgency that transforms what could be ponderous church music into something that practically vibrates with energy. The Monteverdi Choir attacks Bach's intricate polyphony with the precision of a Formula One pit crew, yet never sacrifices the emotional core that makes this music transcendent rather than merely academic.

The album's crown jewel has to be the "Sanctus," where Gardiner unleashes the full power of his forces in a blaze of D major glory that could wake the dead. The way the choir navigates Bach's impossible vocal writing—six parts weaving in and out like some cosmic DNA helix—is simply breathtaking. Close behind is the "Crucifixus," a chromatic descent into darkness so profound it makes Johnny Cash's late albums sound cheerful by comparison. Nancy Argenta's soprano floats above the ensemble like a ghost, while the continuo line walks downward with the inexorability of fate itself.

But it's in moments like the "Et incarnatus est" where Gardiner's interpretive genius truly shines. Rather than treating Bach's word-painting as mere academic exercise, he finds the human drama embedded in every melisma. When the choir whispers "et homo factus est" (and was made man), you can practically hear the wonder in their voices at this central Christian mystery.

The soloists deserve special mention—particularly bass David Thomas, whose "Et in spiritum sanctum" combines theological gravitas with surprising nimbleness, and countertenor Michael Chance, who brings an otherworldly quality to his passages that perfectly captures Bach's fusion of the earthly and divine. These aren't opera stars slumming it in church music; they're specialists who understand that Bach's vocal writing requires both technical mastery and spiritual insight.

What makes this recording endure nearly four decades later is how it manages to be both historically informed and emotionally immediate. Gardiner never lets his scholarly credentials get in the way of the music's raw power. When the final "Dona nobis pacem" arrives, recycling the opening "Gratias" music with devastating effect, it feels like both a prayer and a statement of artistic purpose.

The legacy of this recording extends far beyond the early music world. It proved that period performance practice wasn't just an academic curiosity but could unlock emotional depths in familiar works that had been buried under centuries of interpretive sediment. Every conductor who approaches Bach today—whether on period instruments or not—has to reckon with what Gardiner accomplished here.

In an era when classical music often struggles for relevance, this Mass in B Minor stands as proof that the old masters still have the power to stop us in our tracks. It's not just one of the greatest Bach recordings ever made—it's one of the greatest recordings, period. Essential doesn't begin to cover it.

Listen

Login to add to your collection and write a review.

User reviews

- No user reviews yet.