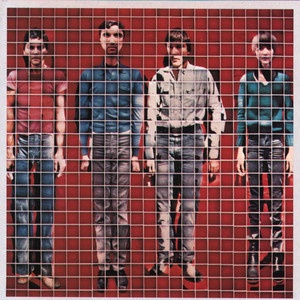

More Songs About Buildings And Food

Review

When David Byrne and his merry band of art-school misfits first stumbled into Compass Point Studios in Nassau during the summer of 1978, they were still finding their feet as a live proposition, having spent two years honing their twitchy, neurotic sound in the dive bars and art galleries of Lower Manhattan. Their debut '77 had been a promising calling card, but it was producer Brian Eno's arrival that would transform Talking Heads from promising post-punk upstarts into something altogether more extraordinary.

Fresh from his groundbreaking work with Roxy Music and his own ambient explorations, Eno brought a magpie's instinct for sonic experimentation that perfectly complemented the band's angular rhythms and Byrne's peculiar worldview. The collaboration wasn't without its tensions – drummer Chris Frantz later admitted to initial scepticism about the producer's methods – but the results speak for themselves. More Songs About Buildings And Food remains a masterclass in how to expand a band's palette without losing their essential DNA.

Musically, the album finds Talking Heads caught between worlds, their CBGB's punk credentials still intact but increasingly informed by Eno's love of African polyrhythms, dub reggae, and electronic textures. Opening track "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)" – their inspired take on Sly Stone's funk classic – immediately signals intent, transforming the original's sweaty groove into something altogether more cerebral and claustrophobic. Byrne's vocals, always an acquired taste, here find their perfect register: part paranoid android, part sociology lecturer having a nervous breakdown.

The album's twin peaks arrive with "Take Me to the River" and "The Big Country." The former, Al Green's gospel-soul classic, becomes something genuinely unsettling in Talking Heads' hands. Where Green found spiritual transcendence, Byrne discovers only anxiety and displacement, his delivery suggesting a man being dragged to salvation against his will. Tina Weymouth's bass work here is particularly inspired, providing both anchor and propulsion while Jerry Harrison's keyboards add layers of unease. It's a cover version that completely reimagines its source material while somehow remaining utterly faithful to its emotional core.

"The Big Country" finds Byrne at his most sardonic, observing American suburban sprawl from an airplane window with the detached fascination of an anthropologist studying an alien civilization. "Good points, some bad points," he observes with characteristic understatement, while the band constructs a hypnotic groove that somehow makes middle-American mundanity sound genuinely mysterious. It's perhaps the clearest statement of the band's unique perspective: finding the extraordinary in the everyday, the alien in the familiar.

Elsewhere, "Warning Sign" showcases the band's growing confidence with dynamics and space, building from whispered paranoia to full-blown anxiety attack, while "Artists Only" prefigures the dance-punk explosion by two decades with its insistent rhythmic pulse and Byrne's stream-of-consciousness observations about creative pretension. Even the album's lesser moments – "The Good Thing" and "I'm Not in Love" – benefit from Eno's production, which adds depth and texture to what might otherwise have been merely clever songs.

The influence of More Songs About Buildings And Food can be heard everywhere in the decades that followed, from the post-punk revival of the early 2000s to the current wave of art-rock experimentalists. LCD Soundsystem's James Murphy has frequently cited it as a touchstone, while bands like Vampire Weekend and Arcade Fire clearly learned from its example of how to be intellectually rigorous without sacrificing emotional impact.

Perhaps most importantly, the album established the template for what Talking Heads would become: a band capable of making dance music for people who thought too much, pop songs for the academically inclined, and art-rock for people who actually wanted to move their bodies. In an era when punk was already calcifying into orthodoxy, Byrne and company suggested that the real rebellion might lie not in three-chord simplicity but in embracing complexity, contradiction, and the beautiful strangeness of modern life.

Four decades on, More Songs About Buildings And Food sounds less like a period piece than a dispatch from a parallel present, one where intellectual curiosity and rhythmic sophistication weren't mutually exclusive. In a world increasingly obsessed with buildings and food – gentrification and gastropubs, anyone? – Byrne's anxious observations feel more prescient than ever.

Listen

Login to add to your collection and write a review.

User reviews

- No user reviews yet.