10cc

Biography

In the pantheon of British pop eccentrics, few bands have matched the sheer audacious brilliance of 10cc, a quartet of studio wizards who emerged from Manchester in the early 1970s wielding an arsenal of hooks, harmonies, and hilariously twisted wordplay that would make the Beatles weep with envy. Born from the ashes of various Stockport-based groups, 10cc represented the convergence of four formidable talents: Graham Gouldman, the hit-making machine who'd already penned classics for The Hollies and The Yardbirds; Kevin Godley and Lol Creme, the experimental masterminds with a shared obsession for sonic innovation; and Eric Stewart, the melodic genius whose voice could soar from tender croon to falsetto perfection.

The band's genesis lay in Strawberry Studios, their Stockport sanctuary where they'd honed their craft as session musicians and producers throughout the late sixties. It was here, amid banks of cutting-edge equipment and clouds of creative smoke, that they discovered their collective genius for crafting immaculate pop confections that were simultaneously commercial and completely barking mad. The name 10cc itself allegedly derived from the average male ejaculation volume – a typically cheeky piece of mythology that the band never definitively confirmed or denied, preferring to let the legend marinate in its own mischievous ambiguity.

Their 1972 debut single "Donna" announced their arrival with a doo-wop pastiche so perfectly executed it fooled radio programmers into thinking they'd unearthed a lost fifties gem. But 10cc were just getting warmed up. The follow-up, "Rubber Bullets," showcased their ability to wrap subversive social commentary in irresistible pop packaging, while "The Dean and I" demonstrated their mastery of intricate vocal arrangements that would make The Beach Boys' Brian Wilson reach for his notepad.

The band's creative peak arrived with 1975's "I'm Not in Love," a six-minute opus of romantic ambivalence that redefined what pop music could achieve. Built on a foundation of layered vocals – reportedly 256 individual voice parts – the track was both a technical marvel and an emotional masterpiece, its whispered confessions and ethereal textures creating an atmosphere of such intimate vulnerability that it still stops listeners dead in their tracks nearly five decades later. The song's innovative use of the Mellotron and multitracking techniques influenced countless artists and established 10cc as pioneers of studio-as-instrument philosophy.

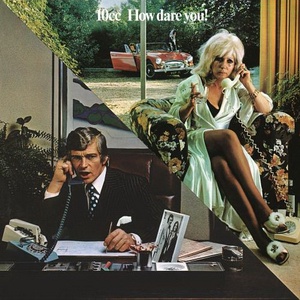

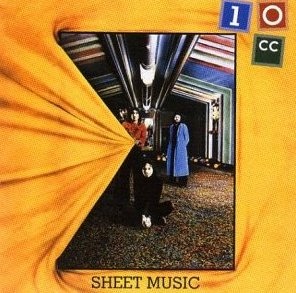

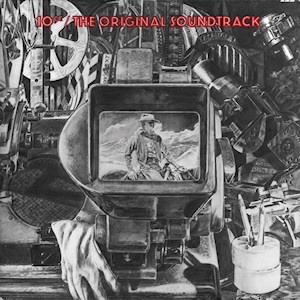

Their albums throughout the mid-seventies – "Sheet Music," "The Original Soundtrack," and "How Dare You!" – revealed a band operating at the absolute pinnacle of their powers, seamlessly blending art rock ambition with pop sensibility. Tracks like "Wall Street Shuffle" skewered capitalism with infectious brass arrangements, while "Art for Art's Sake" served as both manifesto and self-aware commentary on their own creative process. The band's videos, often directed by Godley and Creme themselves, were equally innovative, presaging the MTV era with their cinematic scope and surreal imagery.

The inevitable creative tensions that fuel great bands eventually led to a split in 1976, with Godley and Creme departing to pursue increasingly experimental projects, including the development of the Gizmo, a device that transformed guitar sounds in ways that would later influence entire genres. Stewart and Gouldman continued as 10cc, achieving massive commercial success with 1978's "Dreadlock Holiday," a reggae-tinged narrative that became their biggest UK hit while simultaneously courting controversy for its colonial perspective.

Throughout their career, 10cc accumulated an impressive collection of accolades, including an Ivor Novello Award for "I'm Not in Love" and induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame for Gouldman's broader contributions to popular music. Their influence extended far beyond chart positions, inspiring everyone from Radiohead to Super Furry Animals with their fearless genre-hopping and studio experimentation.

Today, 10cc's legacy stands as testament to an era when pop music could be simultaneously intelligent and accessible, when four lads from Stockport could conquer the world armed with nothing but melody, wit, and an unshakeable belief in the transformative power of the perfect hook. In an industry increasingly dominated by algorithmic predictability, their catalog remains a glorious reminder that the best pop music has always been beautifully, brilliantly, and completely bonkers. Graham