Fats Domino

Biography

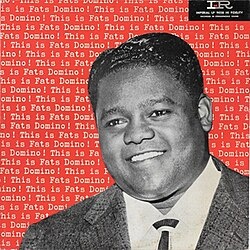

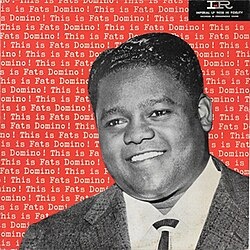

Antoine "Fats" Domino Jr. transformed the landscape of American popular music with his infectious piano-driven rhythm and blues, and nowhere is this magic more evident than on his 1956 masterpiece "This Is Fats Domino!" This album, featuring the irresistible "Blueberry Hill" alongside gems like "Honey Chile" and "What's the Reason I'm Not Pleasing You," perfectly captured the essence of New Orleans R&B while simultaneously helping to birth rock and roll. The record showcased Domino's remarkable ability to blend boogie-woogie piano, Creole rhythms, and his distinctively warm, rolling vocals into something entirely new and utterly captivating.

Born on February 26, 1928, in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans, Antoine Domino grew up in a musical household where his father was a violinist and his brother-in-law, Harrison Verrett, taught him piano. The young Domino absorbed the rich musical gumbo of his hometown – jazz, blues, Creole folk songs, and the infectious second-line rhythms that pulsed through the streets. By his teens, he was already performing in local clubs, his hefty frame earning him the nickname "Fats" that would stick for life.

Domino's professional breakthrough came in 1949 when he met trumpeter and bandleader Dave Bartholomew, who became his longtime collaborator and producer. Their partnership with Imperial Records proved golden, beginning with "The Fat Man," which many music historians consider one of the first true rock and roll records. The song's opening line, "They call me the Fat Man, 'cause I weigh two hundred pounds," delivered in Domino's distinctive drawl over a driving piano rhythm, announced the arrival of a major talent.

Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, Domino became one of the most consistent hitmakers in popular music. His string of classics reads like a rock and roll hall of fame: "Ain't That a Shame," "I'm in Love Again," "Blue Monday," "I'm Walkin'," and "Whole Lotta Loving." These songs showcased his signature style – a rolling, triplet-heavy piano technique that perfectly complemented his laid-back vocal delivery and the tight, horn-driven arrangements crafted by Bartholomew.

What set Domino apart was his ability to make complex musical ideas sound effortless and joyful. His piano playing, influenced by boogie-woogie masters like Albert Ammons and Meade Lux Lewis, featured a distinctive right-hand technique that created an almost lazy, behind-the-beat feel that was irresistibly danceable. His vocals, delivered with a slight Creole accent and an infectious grin you could hear through the speakers, made even heartbreak sound like a good time.

Domino's commercial success was staggering – he sold over 65 million records worldwide and placed 37 songs in the US Top 40 between 1955 and 1963. He was one of the first African American artists to find widespread acceptance among white audiences, helping to break down racial barriers in popular music. His clean-cut image and non-threatening persona made him palatable to nervous parents while his music remained authentically rooted in Black musical traditions.

The accolades followed his success: induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986 as one of its first ten members, a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1987, and the National Medal of Arts in 1998. His influence on subsequent generations of musicians is immeasurable – The Beatles covered his songs, Elvis Presley called him "the real king of rock and roll," and countless pianists from Jerry Lee Lewis to Elton John have acknowledged his impact.

Domino remained remarkably consistent throughout his career, rarely straying from the formula that made him famous. While some criticized this as a lack of artistic growth, others recognized it as the mark of an artist who had achieved perfection in his chosen style. He continued performing well into the 1990s, always returning to his beloved New Orleans between tours.

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 temporarily displaced Domino from his Lower Ninth Ward home, leading to unfounded rumors of his death. He survived the storm and lived quietly in New Orleans until his passing on October 24, 2017, at age 89. His legacy endures not just in his recordings, but in the fundamental role he played in creating the sound that would conquer the