Kate & Anna McGarrigle

Biography

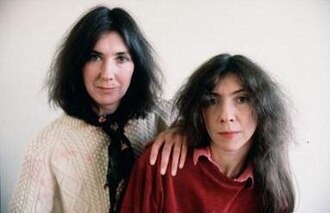

The McGarrigle sisters emerged from the folk-rich landscape of 1960s Montreal like a breath of crystalline mountain air, their voices intertwining with an almost supernatural harmony that would define a career spanning four decades. Kate, born in 1946, and Anna, two years her junior, grew up in a household where French-Canadian folk songs mingled with American country music, creating the cultural cross-pollination that would become their signature.

Their journey began in the coffeehouses of Montreal's Saint-Denis Street, where the sisters honed their craft alongside future luminaries like Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell. But it was their move to New York in the early 1970s that truly launched their careers, though not initially as performers. Kate's songwriting prowess caught the attention of Maria Muldaur, who turned her composition "Work Song" into a minor hit, while Linda Ronstadt's soaring rendition of Kate's "Heart Like a Wheel" became a country-rock classic and the title track of Ronstadt's breakthrough album.

The sisters' 1976 self-titled debut album arrived like a perfectly crafted time capsule, blending traditional folk with contemporary sensibilities. Produced by Joe Boyd, the mastermind behind Fairport Convention and Nick Drake, the record showcased their ability to seamlessly weave between English and French, often within the same song. Kate's "Kiss and Say Goodbye" and Anna's "Complainte pour Ste-Catherine" demonstrated their individual strengths while their harmonies on tracks like "Heart Like a Wheel" revealed an almost telepathic musical connection.

Their sound defied easy categorization – part Appalachian folk, part French chanson, with touches of country, pop, and even classical music. Kate's piano-driven compositions often carried a literary weight, while Anna's accordion work and more traditional folk sensibilities grounded their material in authentic roots music. Their voices, Kate's slightly earthier tone complementing Anna's crystalline clarity, created harmonies that seemed to exist in their own atmospheric space.

The late 1970s and early 1980s saw the McGarrigles at their creative peak. Albums like "Dancer with Bruised Knees" (1977) and "Pronto Monto" (1978) expanded their palette, incorporating elements of cajun music, gospel, and even reggae. Their Christmas album "The McGarrigle Christmas Hour" (1998) became a seasonal classic, featuring their extended musical family including Kate's children Rufus and Martha Wainwright, both destined for their own musical stardom.

The sisters' influence extended far beyond their recorded output. They became cultural ambassadors for French-Canadian music, helping to bridge the gap between Quebec's folk traditions and the broader North American music scene. Their annual Christmas concerts at Montreal's Salle Claude-Champagne became legendary gatherings of the musical cognoscenti, featuring surprise guests and impromptu collaborations that captured the spontaneous spirit of their early coffeehouse days.

Critical acclaim followed them throughout their career, with accolades from publications ranging from Rolling Stone to The New York Times. They received multiple Juno Awards and were inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, recognition that felt long overdue for artists who had influenced a generation of singer-songwriters.

The new millennium brought both triumph and tragedy. Their 2004 album "The McGarrigle Hour" introduced their music to a new generation, while their children's rising fame brought renewed attention to their catalog. However, Kate's battle with cancer cast a shadow over their later years. She continued performing and recording until shortly before her death in January 2010, her final performances displaying the same commitment to musical excellence that had defined her career.

Anna has continued to tour and record, often with Rufus and Martha, keeping the McGarrigle musical legacy alive. Their influence can be heard in artists ranging from Gillian Welch to Arcade Fire, proof that their unique blend of traditional and contemporary, English and French, personal and universal, continues to resonate.

The McGarrigle sisters represented something increasingly rare in popular music – artists who remained true to their vision while never sacrificing accessibility for authenticity. Their music exists in a timeless space where folk traditions meet contemporary songcraft, where familial harmonies transcend mere technique to become something approaching the spiritual. In an era of manufactured music, they offered something genuine, something that could only have emerged from their specific cultural moment and geographical place, yet somehow managed to speak to universal human experiences of love, loss, and the search for home.